Spot on Toddy, more a case of "Mead and nibbles (read shell fish) at my place tonight then" in ye olde days. I'm very fond of shellfish but its worse than booze for triggering an attack of gout (but you are allowed Vodka or White Rum), so no more pickled cockles and black pepper sarnies for me at the moment

What would you do for food?

- Thread starter stu1979uk

- Start date

-

Come along to the amazing Summer Moot (21st July - 2nd August), a festival of bushcrafting and camping in a beautiful woodland PLEASE CLICK HERE for more information.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

If it was life or death at Loch Lomond I'd probably wait for the rangers to come back round and get a lift back to the car

Saying that though there's plenty of deer, wallabies, swans, geese, sheep, goats, squirrels and fish about to keep me going for a few days. The wallabies and swans would be the easiest to catch so I'd probably start with them. Then get a few night lines chucked out for the pike using the innards for bait, plenty of line caught up in the trees and a hook should be doable with some small bones.

Saying that though there's plenty of deer, wallabies, swans, geese, sheep, goats, squirrels and fish about to keep me going for a few days. The wallabies and swans would be the easiest to catch so I'd probably start with them. Then get a few night lines chucked out for the pike using the innards for bait, plenty of line caught up in the trees and a hook should be doable with some small bones.

Ok then, for extending the trip in the Trossachs a day or two, fling some fishing lines out or set some snares (permission obtained of course) and see what they return, what about foraging plants for short term?

Cat tail plant often seen on RM programmes easily identified and looks as if it would be good return for effort to obtain. What other plants are readily available and are filling?

As for longer term heading for the sea would make sense especially with a river running in as ste carey suggests, although I'll need to sus out what type of plants are eddible on the coast.

sandbender- Sounds like a limited supply trip for next year as you suggest go out and try it best way to learn.

Cheers for the replies all

Stuart

Cat tail plant often seen on RM programmes easily identified and looks as if it would be good return for effort to obtain. What other plants are readily available and are filling?

As for longer term heading for the sea would make sense especially with a river running in as ste carey suggests, although I'll need to sus out what type of plants are eddible on the coast.

sandbender- Sounds like a limited supply trip for next year as you suggest go out and try it best way to learn.

Cheers for the replies all

Stuart

I have already posted about this a while back, but in short; my Dad lived wild on Rannoch Moor for three years while he recovered from rheumatic fever in the 1930's.

No National Health, no Sickness Benefit and his parents had three other children in apprenticeships.

He had just finished his time as a joiner and he took a small pack, an ex army pup tent and a small toolkit. That was it.

When he was ill he stayed in his bed, when he was fit he foraged, hunted and did a bit of work for the local farmers. No one had any extra money, but their wives saw him all right for eggs, bacon, cheese, butter in season, oatmeal and potatoes. He guddled for fish (much to the disdain of the anglers and he caught more than they did) he snared rabbits (only works if you know where they run) and took a few other birds and beasts as he chanced on them.

and he caught more than they did) he snared rabbits (only works if you know where they run) and took a few other birds and beasts as he chanced on them.

He lost a lot of weight, but he was never fitter in his life.

He said that without the farmers wives, he'd have gone damned hungry.

I know how good my Dad was at this game. If he couldn't make it thrive, living there and knowing the land in all it's seasons, you won't.

I think we could do it for a while, but it really needs group cooperation to take down the big game, the deer hunts, the seal hunts, time after time after time.

We need to farm to survive for long in our climate. Otherwise seasonal starvation will get you, especially if there isn't a huge foraging area available.

cheers,

Toddy

No National Health, no Sickness Benefit and his parents had three other children in apprenticeships.

He had just finished his time as a joiner and he took a small pack, an ex army pup tent and a small toolkit. That was it.

When he was ill he stayed in his bed, when he was fit he foraged, hunted and did a bit of work for the local farmers. No one had any extra money, but their wives saw him all right for eggs, bacon, cheese, butter in season, oatmeal and potatoes. He guddled for fish (much to the disdain of the anglers

He lost a lot of weight, but he was never fitter in his life.

He said that without the farmers wives, he'd have gone damned hungry.

I know how good my Dad was at this game. If he couldn't make it thrive, living there and knowing the land in all it's seasons, you won't.

I think we could do it for a while, but it really needs group cooperation to take down the big game, the deer hunts, the seal hunts, time after time after time.

We need to farm to survive for long in our climate. Otherwise seasonal starvation will get you, especially if there isn't a huge foraging area available.

cheers,

Toddy

I think Toddy is spot on.

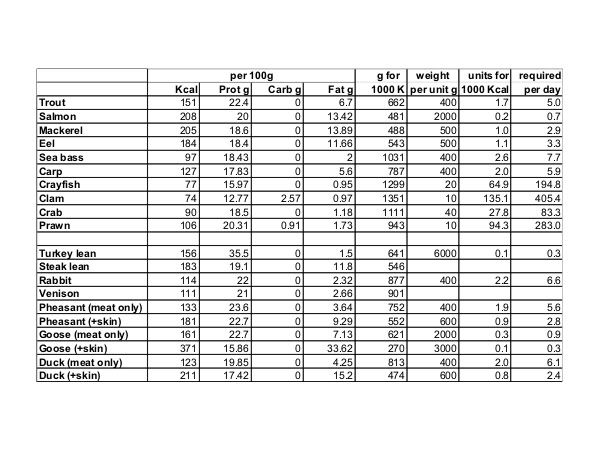

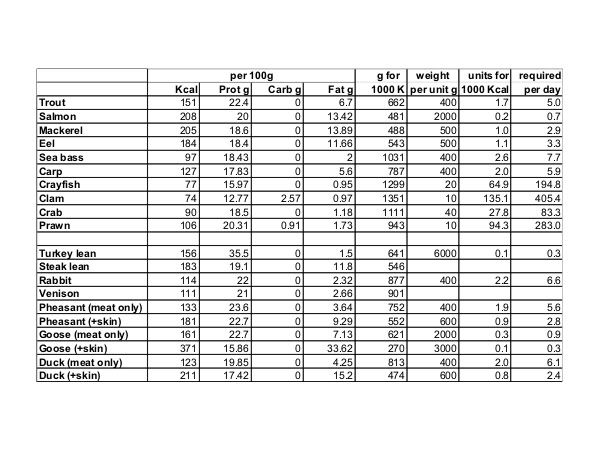

I did some work on this a while back to try and determine how much of what kinds of food you need to catch, prepare, and eat to survive. I came to the conclusion that one person on their own would struggle and probably not survive. That same person would have to cut logs for fire and build and maintain shelter at the same time. The following table shows the calorific value of food we may catch/trap. It then works through the figures and comes up with an estimate for how many a day you would need to eat based on 3000kcals - and that would be the minimum if you were living off your skills in the wild. It ignores the fact that you woudl have to mix your diet to stay healthy.

So, for example, you would need to eat only three mackerel a day (easy for the odd day or so in summer), or nearlly 200 crayfish, or 300 prawns - I'll let you work the rest out.

Cheers,

Broch

I did some work on this a while back to try and determine how much of what kinds of food you need to catch, prepare, and eat to survive. I came to the conclusion that one person on their own would struggle and probably not survive. That same person would have to cut logs for fire and build and maintain shelter at the same time. The following table shows the calorific value of food we may catch/trap. It then works through the figures and comes up with an estimate for how many a day you would need to eat based on 3000kcals - and that would be the minimum if you were living off your skills in the wild. It ignores the fact that you woudl have to mix your diet to stay healthy.

So, for example, you would need to eat only three mackerel a day (easy for the odd day or so in summer), or nearlly 200 crayfish, or 300 prawns - I'll let you work the rest out.

Cheers,

Broch

Toddy,

I assume these are shelled small oysters eaten raw. If I'm right then we are talking approx one and a half pound not so bad.

700 small oysters = one and a half pound? so 4900 oysters for a week, around five kilo and you only need one bad one to knock you out of action or worse.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3s-O29k4mzc

That's really useful thanks Broch, mind if I print a few out ?

I could happily live on Salmon and Goose I reckon

Be my guest.

I'm not sure I could stomach all that goose fat though

Cheers,

Broch

He said that without the farmers wives, he'd have gone damned hungry.

Aye, I've seen a few that looked like there was good eating on 'em...

Sorry.

My Dad would have laughed at that too

One of the farmers was keen enough to keep him in the family (handy fellows joiners) that he offered to marry him off to any of his three daughters

I think that's when Dad decided it was time to come home.......

M

Rik uk

You could fall over break your leg, same thing. I just used the oyster as an example I never said you could live on oysters alone.

? sorry don't understand.

dogs cats rats would all be on the run and hence on the menu.

i think you could get away without farming if you made good of preserving stuff when the bounty was good salting smoking and drying stock but in short i would expect a great deal of canabolism going on, one thing i cannot stand is hunger i have a fast metabolism and get through 3 - 6000 cals a day i am sure there is not enough resources in the Uk if it all went tits up and in time it would be the hard knocks with weapons who would roam the land and perhaps the odd sneaky bushcrafter who avoids detection.

i think you could get away without farming if you made good of preserving stuff when the bounty was good salting smoking and drying stock but in short i would expect a great deal of canabolism going on, one thing i cannot stand is hunger i have a fast metabolism and get through 3 - 6000 cals a day i am sure there is not enough resources in the Uk if it all went tits up and in time it would be the hard knocks with weapons who would roam the land and perhaps the odd sneaky bushcrafter who avoids detection.

personally i would be trapping and hunting in the big cities.

realistically, how many people who live in cities would have the first idea of how to survive? barely any, and those who do (like members on here) would all be down the beach eating 700 limpets a day, while the foxes and pigeons re-claim the cities and arent hunted because barely anyone in a city would know how.

also, you wouldnt have trouble finding shelter in a city like london.

however it might be a good idea to wait a year after the zombie invasion or whatever so that all the rioters and people who are clueless have died and all that is left are the groups of people who have learnt to survive.

then start repopulating!

realistically, how many people who live in cities would have the first idea of how to survive? barely any, and those who do (like members on here) would all be down the beach eating 700 limpets a day, while the foxes and pigeons re-claim the cities and arent hunted because barely anyone in a city would know how.

also, you wouldnt have trouble finding shelter in a city like london.

however it might be a good idea to wait a year after the zombie invasion or whatever so that all the rioters and people who are clueless have died and all that is left are the groups of people who have learnt to survive.

then start repopulating!

? sorry don't understand.

Sorry I don't explain. I did like the youtube link thou

Rabbits are poor survival food, no fat to speak of and limpets ? You would need to eat several kilo a day for any real food value. Form a group, forage, loot and start farming. Spear a deer? easy, I trip over the bloody things here in Wales everyday.

Spot on about rabbits. In fact there is a known condition called rabbit starvation.

I read once of American settlers starving to death despite eating numerous rabbits to the exclusion of any plantlife which would have saved them. How true this story was I don't know but it is accepted that you would suffer extreme diahorrea, headache and lethagy within a week. Some theorise that you would die quicker then if you ate nothing but there is a distinct lack of volunteers to substantiate!!

From Antiquity, an archaeological journal.

The bold paragraph is my emphasis.

Against the grain? A response to Milner et al. (2004)

Introduction

A recent publication in this journal (Milner et al. 2004) called into question the increasing body of human stable isotopic data showing a rapid diet shift away from marine resources associated with the beginning of the Neolithic in parts of north-western Europe, particularly in Britain and Denmark. While we very much welcome informed and positive debate on this issue, we feel we must respond to this specific paper as it is problematic at a number of levels.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis of human bone is beginning to challenge what we would argue is the current orthodoxy of a gradual dietary transition between the Mesolithic and Neolithic. Indeed, the stable isotope data support some elements of a previous orthodoxy, which saw the advent of the Neolithic as a 'revolution'. This is not to say that all elements are supported by the isotopic data; the question of the interactions between any incomers and indigenous people, for example, is still very much a live issue. And it is still far from clear exactly how the shift occurred, how rapid it was in human terms (in generations rather than radiocarbon years), and why it occurred. And there is still the possibility of regional and supra-regional variation to be addressed fully. But the implications of the stable isotope data are beginning to be acknowledged and addressed (e.g. Thomas 2003). This is an important independent line of evidence, and has been available since the early 1980s (Tauber 1981a), yet until recently little consideration has been given to the picture of a very rapid and significant shift in diet across the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition. Instead, it is during this very period that the view of the transition as a long, drawn-out process began to emerge and dominate discussion (Thomas 1991).

It is in this context that criticisms made of the isotopic data, particularly by Milner et al. (2004) need to be addressed. Their dismissal of the isotopic evidence for a rapid and significant transition, while to some extent encouraging debate, also prematurely attempts to close it. Milner et al. (2004) present their critique along three main fronts (see also Bailey & Milner 2002). Firstly, they contend that the zooarchaeological and archaeological evidence for diet is at odds with the stable isotope data; secondly, they point to problems of sample size and bias in the human skeletons used for analysis; and thirdly, they argue that there are problems with the interpretation of stable isotope data. We address each of these concerns in turn.

The (zoo)archaeological data

Milner et al. (2004) make much of the zooarchaeological evidence for the continued use of marine resources in the Neolithic, taking examples mainly from Denmark but also from Britain and Ireland. They argue that the presence of the remains of marine foods (especially shellfish) in Neolithic contexts, and the occurrence of apparent seal-hunting stations and of fish traps, somehow counters any argument of a large-scale dietary shift at the start of the Neolithic. Despite the numerous problems and biases with the use of zooarchaeological data, they present this evidence as if it were some sort of 'spoiler'; that finding any evidence, however slight, of any Neolithic person consuming marine foods undermines the isotopic data of a large scale shift. Simply put, the continued occasional use of marine resources in the Neolithic is not at all incompatible with the isotope data, but is largely irrelevant in the overall question of large-scale dietary shifts. The isotopic evidence presents a long-term measure of lifetime diets, and clearly shows a significant change in human diet between the Mesolithic and the Neolithic. Remains of fish and shellfish recovered from archaeological sites are the remains of individual meals, but are not indicative of the overall diet of a human population. As Geoff Bailey himself has elegantly argued (Bailey 1975, 1978), shells are highly visible archaeologically due to their preservational properties, but misleading in terms of determining diet composition, as they are nutritionally poor. Bailey (1978) writes that:

'The ease with which molluscs can be over-rated as a source of food will be swiftly appreciated from the fact that approximately 700 oysters would be needed to supply enough kilocalories for one person for one day, if no other food were eaten, or 1400 cockles, or 400 limpets, to name the species most often found in European middens. I have estimated that approximately 52,267 oysters would be required to supply the calorific equivalent of a single red deer carcase, 156,800 cockles, or 31,360 limpets, figures which may help to place in proper nutritional perspective the vast numbers of shells recorded archaeologically.' (Bailey 1978: 39, emphasis ours) Therefore, the occasional Neolithic shell midden is in itself hardly indicative of a continued marine-based economy in this period. The nature of the exploitation may have been very different, for example, from a central aspect of subsistence in the Mesolithic to one more peripheral in the Neolithic.

In addition, it should be emphasised that, aside from these shell middens and special purpose sites, there are actually very few Neolithic faunal assemblages known from Denmark. Bone survival is poor away from the shell middens, but where mammalian fauna is preserved from the Early Neolithic, it is dominated by domestic fauna (see Fischer 2002 for a recent review). Thus Milner et al.'s (2004) discussion touches upon only one aspect of the Neolithic economy, and likely a very limited one.

In the context of Britain, where much of our own research on this issue has been focused (i.e. Richards & Hedges 1999; Richards et al. 2003a; Schulting & Richards 2002a, b), Milner et al. (2004) do agree that there is substantially less evidence for marine exploitation in the Neolithic. They suggest that this is partly because of inundation of coastal sites by rising sea levels. However, sea levels were quite close to their present position by 4000 cal BC (the generally accepted data for the appearance of Neolithic material culture in the UK), so that this argument holds far less relevance than it does for the Mesolithic period, when it is very much a factor (Schulting & Richards 2002a, b). Milner et al. point to shell middens of Neolithic date along the Firth of Forth in south-east Scotland and along the coast of Co. Sligo, western Ireland, and to evidence for fishing from Neolithic Orkney. The shell middens are subject to the same issues already raised above--their simple presence, while certainly interesting and worthy of further investigation--says little about their quantitative importance in long-term diet. The Forth and Sligo middens are notable for the absence of much in the way of cultural material, or indeed …

Thanks for that - got a link please?

So just because the human race has gone loco....all the live stock has too???...NAAAAAHH!,

I'd be down my local farm livin it up on moo steaks and Baaaa legs....YUM YUM YUM....when is the world ending (i'm hungry)

I'd be down my local farm livin it up on moo steaks and Baaaa legs....YUM YUM YUM....when is the world ending (i'm hungry)

Similar threads

- Replies

- 23

- Views

- 790

- Replies

- 88

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 15

- Views

- 540

- Replies

- 118

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 16

- Views

- 454