Beginner Bushcraft Knife and Axe recommendations

- Thread starter Lpknight92

- Start date

-

Come along to the amazing Summer Moot (21st July - 2nd August), a festival of bushcrafting and camping in a beautiful woodland PLEASE CLICK HERE for more information.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

so how does a group of youths manage on guy fawkes night?.....sorry but the comtrol a fire issue??....when theres all manner of sizes of timber?I don't mean to be rude, but you are showing a great deal of ignorance about maintaining any kind of fire used for a group.

And yes, if we are 'journeying' solo we carry the means to boil water and eat without a large fire. At a camp, and where it's viable, a well maintained fire is the heart and sole of being in the wild. There are still plenty of places that's possible even on this overcrowded island.

fun to split yes ABSOLUTELY

required though,??

oh and...glad i joined here the responses are great thanks.

my thoughts on bushcraft and edc remain the same though...

certainly sparked a conversation though ........though i havent seen a situation easily resolved by a victorinoxso how does a group of youths manage on guy fawkes night?.....sorry but the comtrol a fire issue??....when theres all manner of sizes of timber?

fun to split yes ABSOLUTELY

required though,??

oh and...glad i joined here the responses are great thanks.

my thoughts on bushcraft and edc remain the same though..

i agree but my original point is lost...my question is a nd remains...is an axe really required??...or for that matter a full tang knife??...or yes?....even your group open fire??....as my wild camps out??I don't mean to be rude, but you are showing a great deal of ignorance about maintaining any kind of fire used for a group.

And yes, if we are 'journeying' solo we carry the means to boil water and eat without a large fire. At a camp, and where it's viable, a well maintained fire is the heart and sole of being in the wild. There are still plenty of places that's possible even on this overcrowded island.

none are a requirement....we pursue what we see as fun...or a hobby....a group fire isnt required....

i came with the question of "bushcraft" is it a "required" skill relevant here in the uk???......

oh and....i wasnt on about the over 1 inch thick bits lying around your fire....but the bits ranging from pencil size looking up to the bigger bitsl....so whats all the bits around it?....dont they snap??

oh also....i dont think you rude at all...its why im here...to find the answer to my thoughts on bushcraftcertainly sparked a conversation though ........though i havent seen a situation easily resolved by a victorinox

i agree but my original point is lost...my question is a nd remains...is an axe really required??...or for that matter a full tang knife??...or yes?....even your group open fire??....as my wild camps out??

none are a requirement....we pursue what we see as fun...or a hobby....a group fire isnt required....

i came with the question of "bushcraft" is it a "required" skill relevant here in the uk???......

Not read any of this thread - However for an interlude I thought we could ponder and study the origin of the humble Question mark ( ? ) as its quite ubiquitous within this thread.

As readers and writers, we’re intimately familiar with the dots, strokes and dashes that punctuate the written word. The comma, colon, semicolon and their siblings are integral parts of writing, pointing out grammatical structures and helping us transform letters into spoken words or mental images. We would be lost without them (or, at the very least, extremely confused), and yet the earliest readers and writers managed without it for thousands of years. What changed their minds?

In the 3rd Century BCE, in the Hellenic Egyptian city of Alexandria, a librarian named Aristophanes had had enough. He was chief of staff at the city’s famous library, home to hundreds of thousands of scrolls, which were all frustratingly time-consuming to read. For as long as anyone could remember, the Greeks had written their texts so that their letters ran together withnospacesorpunctuation and without any distinction between lowercase and capitals. It was up to the reader to pick their way through this unforgiving mass of letters to discover where each word or sentence ended and the next began.

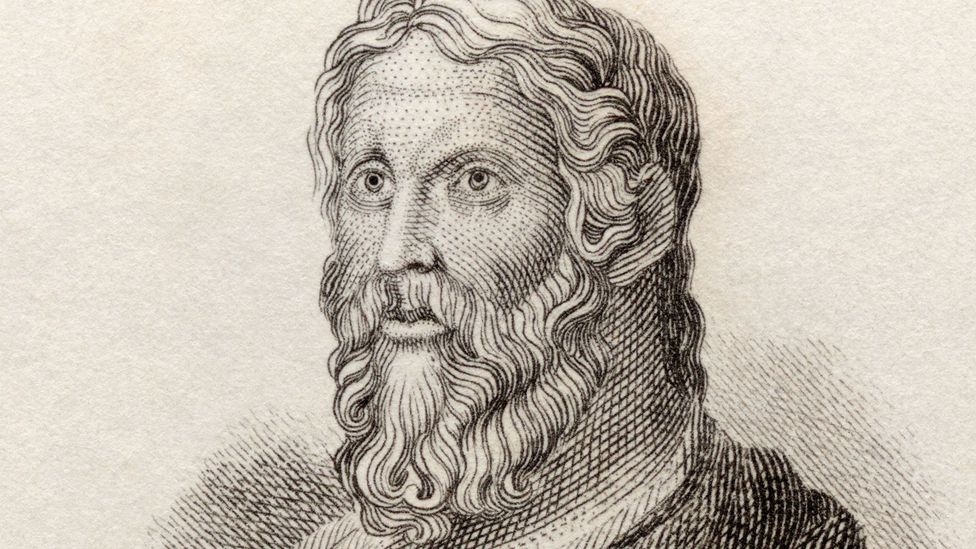

In early Greece and Rome, understanding a text on a first reading was unheard of (Credit: Getty Images)

Joining the dots

Aristophanes’ breakthrough was to suggest that readers could annotate their documents, relieving the unbroken stream of text with dots of ink aligned with the middle (·), bottom (.) or top (·) of each line. His ‘subordinate’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘full’ points corresponded to the pauses of increasing length that a practised reader would habitually insert between formal units of speech called the comma, colon and periodos. This was not quite punctuation as we know it – Aristophanes saw his marks as representing simple pauses rather than grammatical boundaries – but the seed had been planted.

The Romans eventually abandoned Aristophanes’ system of dots without a second thought (Credit: Classic Image / Alamy)

Unfortunately, not everyone was convinced of the value of this new invention. When the Romans overtook the Greeks as the preeminent empire-builders of the ancient world, they abandoned Aristophanes’ system of dots without a second thought. Cicero, for example, one of Rome’s most famous public speakers, told his rapt audiences that the end of a sentence “ought to be determined not by the speaker’s pausing for breath, or by a stroke interposed by a copyist, but by the constraint of the rhythm”.

Writing comes of age

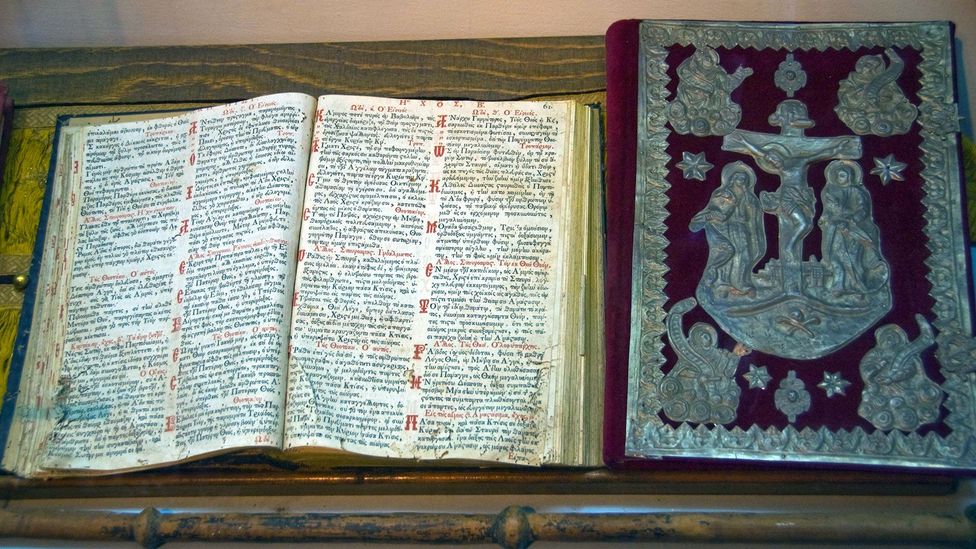

It was the rise of a quite different kind of cult that resuscitated Aristophanes’ foray into punctuation. As the Roman Empire crumbled in the 4th and 5th Centuries, Rome’s pagans found themselves fighting a losing battle against a new religion called Christianity. Whereas pagans had always passed along their traditions and culture by word of mouth, Christians preferred to write down their psalms and gospels to better spread the word of God. Books became an integral part of the Christian identity, acquiring decorative letters and paragraph marks (Γ, ¢, 7, ¶ and others), and many were lavishly illustrated with gold leaf and intricate paintings.

As it spread across Europe, Christianity embraced writing and rejuvenated punctuation. In the 6th Century, Christian writers began to punctuate their own works long before readers got their hands on them in order to protect their original meaning. Later, in the 7th Century, Isidore of Seville (first an archbishop and later beatified to become a saint, though sadly not for his services to punctuation) described an updated version of Aristophanes’ system in which he rearranged the dots in order of height to indicate short (.), medium (·) and long (·) pauses respectively.

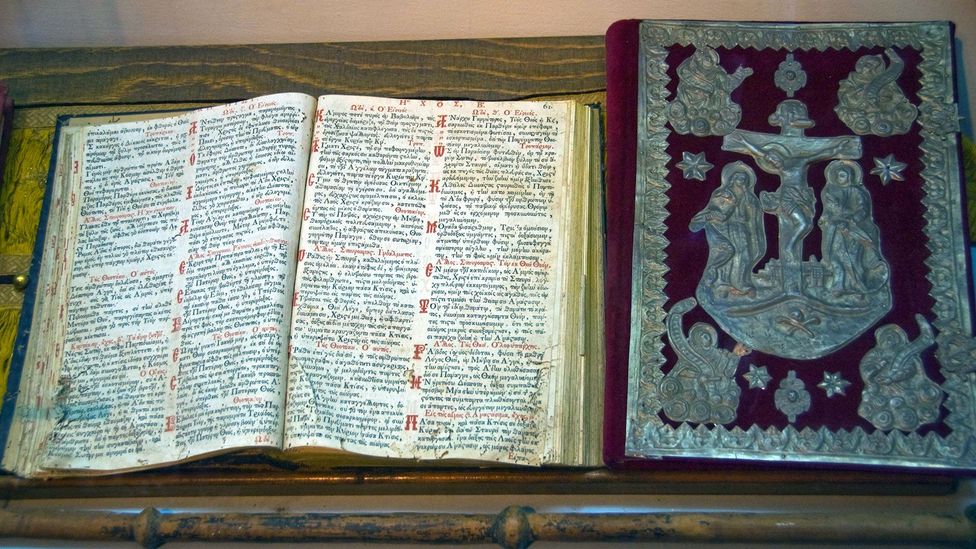

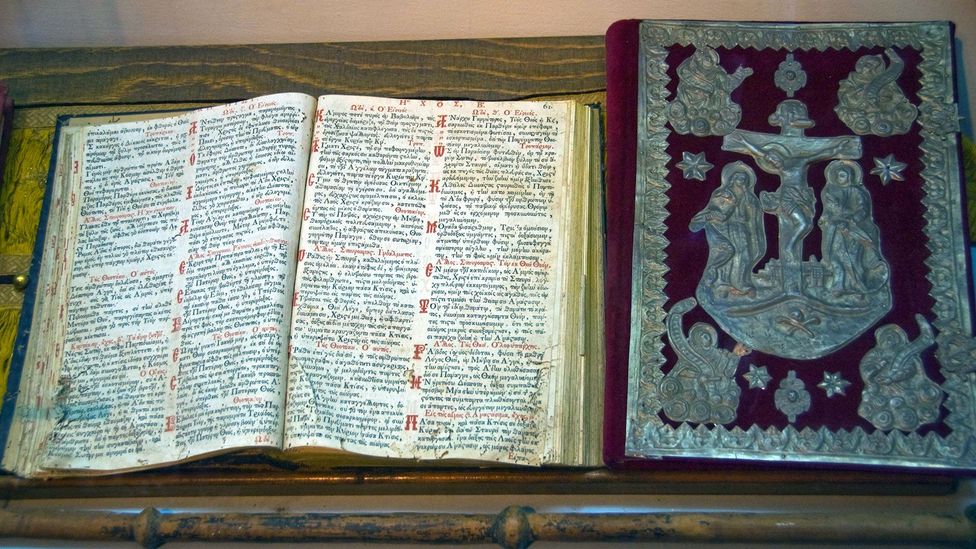

Books became an integral part of the Christian identity, acquiring decorative letters and paragraph marks (Credit: Alamy)

Moreover, Isidore explicitly connected punctuation with meaning for the first time: the re-christened subdistinctio, or low point (.), no longer marked a simple pause but was rather the signpost of a grammatical comma, while the high point, or distinctio finalis (·), stood for the end of a sentence. Spaces between words appeared soon after this, an invention of Irish and Scottish monks tired of prying apart unfamiliar Latin words. And towards the end of the 8th Century, in the nascent country of Germany, the famed king Charlemagne ordered a monk named Alcuin to devise a unified alphabet of letters that could be read by all his far-flung subjects, thus creating what we now know as lowercase letters. Writing had come of age, and punctuation was an indispensable part of it.

Cutting a dash

With Aristophanes’ little dots now commonplace, writers began to expand on them. Some borrowed from musical notation, inspired by Gregorian chants to create new marks like the punctus versus (a medieval ringer for the semicolon used to terminate a sentence) and the punctus elevatus (an upside-down ‘;’ that evolved into the modern colon) that suggested changes in tone as well as grammatical meaning. Another new mark, an ancestor of the question mark called the punctus interrogativus, was used to punctuate questions and to convey a rising inflection at the same time (The related exclamation mark came later, during the 15th Century.)

The three dots that had spawned punctuation in the first place inevitably suffered as a result. As other, more specific symbols were created, the distinction between low, medium and high points grew indistinct until all that was left was a simple point that could be placed anywhere on the line to indicate a pause of indeterminate length – a muddied mixture of the comma, colon and full stop. The humble dot was put under pressure on another front, too, when a 12th Century Italian writer named Boncompagno da Signa proposed an entirely new system of punctuation comprising only two marks: a slash (/) represented a pause while a dash (—) terminated sentences. The fate of da Signa’s dash is murky – it may or may not be the ancestor of the parenthetical dash, like those that surround these words – but the slash, or virgula suspensiva, was an unequivocal success. It was compact and visually distinctive, and it soon began to edge out the last holdouts of Aristophanes’s system as a general-purpose comma or pause.

As readers and writers, we’re intimately familiar with the dots, strokes and dashes that punctuate the written word. The comma, colon, semicolon and their siblings are integral parts of writing, pointing out grammatical structures and helping us transform letters into spoken words or mental images. We would be lost without them (or, at the very least, extremely confused), and yet the earliest readers and writers managed without it for thousands of years. What changed their minds?

In the 3rd Century BCE, in the Hellenic Egyptian city of Alexandria, a librarian named Aristophanes had had enough. He was chief of staff at the city’s famous library, home to hundreds of thousands of scrolls, which were all frustratingly time-consuming to read. For as long as anyone could remember, the Greeks had written their texts so that their letters ran together withnospacesorpunctuation and without any distinction between lowercase and capitals. It was up to the reader to pick their way through this unforgiving mass of letters to discover where each word or sentence ended and the next began.

Yet the lack of punctuation and word spaces was not seen as a problem. In early democracies such as Greece and Rome, where elected officials debated to promote their points of view, eloquent and persuasive speech was considered more important than written language and readers fully expected that they would have to pore over a scroll before reciting it in public. To be able to understand a text on a first reading was unheard of: when asked to read aloud from an unfamiliar document, a 2nd Century writer named Aulus Gellius protested that he would mangle its meaning and emphasise its words incorrectly. (When a bystander stepped in to read the document instead, he did just that.)In early Greece and Rome, persuasive speech was more important than written language

In early Greece and Rome, understanding a text on a first reading was unheard of (Credit: Getty Images)

Joining the dots

Aristophanes’ breakthrough was to suggest that readers could annotate their documents, relieving the unbroken stream of text with dots of ink aligned with the middle (·), bottom (.) or top (·) of each line. His ‘subordinate’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘full’ points corresponded to the pauses of increasing length that a practised reader would habitually insert between formal units of speech called the comma, colon and periodos. This was not quite punctuation as we know it – Aristophanes saw his marks as representing simple pauses rather than grammatical boundaries – but the seed had been planted.

The Romans eventually abandoned Aristophanes’ system of dots without a second thought (Credit: Classic Image / Alamy)

Unfortunately, not everyone was convinced of the value of this new invention. When the Romans overtook the Greeks as the preeminent empire-builders of the ancient world, they abandoned Aristophanes’ system of dots without a second thought. Cicero, for example, one of Rome’s most famous public speakers, told his rapt audiences that the end of a sentence “ought to be determined not by the speaker’s pausing for breath, or by a stroke interposed by a copyist, but by the constraint of the rhythm”.

And though the Romans had experimented for a while with separating·words·with·dots, by the second century CE they had abandoned that too. The cult of public speaking was a strong one, to the extent that all reading was done aloud: most scholars agree that the Greeks and Romans got round their lack of punctuation by murmuring aloud as they read through texts of all kinds.Books became an integral part of the Christian identity

Writing comes of age

It was the rise of a quite different kind of cult that resuscitated Aristophanes’ foray into punctuation. As the Roman Empire crumbled in the 4th and 5th Centuries, Rome’s pagans found themselves fighting a losing battle against a new religion called Christianity. Whereas pagans had always passed along their traditions and culture by word of mouth, Christians preferred to write down their psalms and gospels to better spread the word of God. Books became an integral part of the Christian identity, acquiring decorative letters and paragraph marks (Γ, ¢, 7, ¶ and others), and many were lavishly illustrated with gold leaf and intricate paintings.

As it spread across Europe, Christianity embraced writing and rejuvenated punctuation. In the 6th Century, Christian writers began to punctuate their own works long before readers got their hands on them in order to protect their original meaning. Later, in the 7th Century, Isidore of Seville (first an archbishop and later beatified to become a saint, though sadly not for his services to punctuation) described an updated version of Aristophanes’ system in which he rearranged the dots in order of height to indicate short (.), medium (·) and long (·) pauses respectively.

Books became an integral part of the Christian identity, acquiring decorative letters and paragraph marks (Credit: Alamy)

Moreover, Isidore explicitly connected punctuation with meaning for the first time: the re-christened subdistinctio, or low point (.), no longer marked a simple pause but was rather the signpost of a grammatical comma, while the high point, or distinctio finalis (·), stood for the end of a sentence. Spaces between words appeared soon after this, an invention of Irish and Scottish monks tired of prying apart unfamiliar Latin words. And towards the end of the 8th Century, in the nascent country of Germany, the famed king Charlemagne ordered a monk named Alcuin to devise a unified alphabet of letters that could be read by all his far-flung subjects, thus creating what we now know as lowercase letters. Writing had come of age, and punctuation was an indispensable part of it.

Cutting a dash

With Aristophanes’ little dots now commonplace, writers began to expand on them. Some borrowed from musical notation, inspired by Gregorian chants to create new marks like the punctus versus (a medieval ringer for the semicolon used to terminate a sentence) and the punctus elevatus (an upside-down ‘;’ that evolved into the modern colon) that suggested changes in tone as well as grammatical meaning. Another new mark, an ancestor of the question mark called the punctus interrogativus, was used to punctuate questions and to convey a rising inflection at the same time (The related exclamation mark came later, during the 15th Century.)

The three dots that had spawned punctuation in the first place inevitably suffered as a result. As other, more specific symbols were created, the distinction between low, medium and high points grew indistinct until all that was left was a simple point that could be placed anywhere on the line to indicate a pause of indeterminate length – a muddied mixture of the comma, colon and full stop. The humble dot was put under pressure on another front, too, when a 12th Century Italian writer named Boncompagno da Signa proposed an entirely new system of punctuation comprising only two marks: a slash (/) represented a pause while a dash (—) terminated sentences. The fate of da Signa’s dash is murky – it may or may not be the ancestor of the parenthetical dash, like those that surround these words – but the slash, or virgula suspensiva, was an unequivocal success. It was compact and visually distinctive, and it soon began to edge out the last holdouts of Aristophanes’s system as a general-purpose comma or pause.

interesting read.....thanks.can you imagine trying to read these posts if they were written without spaces? it threw me slightly just reading your exampleNot read any of this thread - However for an interlude I thought we could ponder and study the origin of the humble Question mark ( ? ) as its quite ubiquitous within this thread.

View attachment 68406

As readers and writers, we’re intimately familiar with the dots, strokes and dashes that punctuate the written word. The comma, colon, semicolon and their siblings are integral parts of writing, pointing out grammatical structures and helping us transform letters into spoken words or mental images. We would be lost without them (or, at the very least, extremely confused), and yet the earliest readers and writers managed without it for thousands of years. What changed their minds?

In the 3rd Century BCE, in the Hellenic Egyptian city of Alexandria, a librarian named Aristophanes had had enough. He was chief of staff at the city’s famous library, home to hundreds of thousands of scrolls, which were all frustratingly time-consuming to read. For as long as anyone could remember, the Greeks had written their texts so that their letters ran together withnospacesorpunctuation and without any distinction between lowercase and capitals. It was up to the reader to pick their way through this unforgiving mass of letters to discover where each word or sentence ended and the next began.

Yet the lack of punctuation and word spaces was not seen as a problem. In early democracies such as Greece and Rome, where elected officials debated to promote their points of view, eloquent and persuasive speech was considered more important than written language and readers fully expected that they would have to pore over a scroll before reciting it in public. To be able to understand a text on a first reading was unheard of: when asked to read aloud from an unfamiliar document, a 2nd Century writer named Aulus Gellius protested that he would mangle its meaning and emphasise its words incorrectly. (When a bystander stepped in to read the document instead, he did just that.)

In early Greece and Rome, understanding a text on a first reading was unheard of (Credit: Getty Images)

Joining the dots

Aristophanes’ breakthrough was to suggest that readers could annotate their documents, relieving the unbroken stream of text with dots of ink aligned with the middle (·), bottom (.) or top (·) of each line. His ‘subordinate’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘full’ points corresponded to the pauses of increasing length that a practised reader would habitually insert between formal units of speech called the comma, colon and periodos. This was not quite punctuation as we know it – Aristophanes saw his marks as representing simple pauses rather than grammatical boundaries – but the seed had been planted.

The Romans eventually abandoned Aristophanes’ system of dots without a second thought (Credit: Classic Image / Alamy)

Unfortunately, not everyone was convinced of the value of this new invention. When the Romans overtook the Greeks as the preeminent empire-builders of the ancient world, they abandoned Aristophanes’ system of dots without a second thought. Cicero, for example, one of Rome’s most famous public speakers, told his rapt audiences that the end of a sentence “ought to be determined not by the speaker’s pausing for breath, or by a stroke interposed by a copyist, but by the constraint of the rhythm”.

And though the Romans had experimented for a while with separating·words·with·dots, by the second century CE they had abandoned that too. The cult of public speaking was a strong one, to the extent that all reading was done aloud: most scholars agree that the Greeks and Romans got round their lack of punctuation by murmuring aloud as they read through texts of all kinds.

Writing comes of age

It was the rise of a quite different kind of cult that resuscitated Aristophanes’ foray into punctuation. As the Roman Empire crumbled in the 4th and 5th Centuries, Rome’s pagans found themselves fighting a losing battle against a new religion called Christianity. Whereas pagans had always passed along their traditions and culture by word of mouth, Christians preferred to write down their psalms and gospels to better spread the word of God. Books became an integral part of the Christian identity, acquiring decorative letters and paragraph marks (Γ, ¢, 7, ¶ and others), and many were lavishly illustrated with gold leaf and intricate paintings.

As it spread across Europe, Christianity embraced writing and rejuvenated punctuation. In the 6th Century, Christian writers began to punctuate their own works long before readers got their hands on them in order to protect their original meaning. Later, in the 7th Century, Isidore of Seville (first an archbishop and later beatified to become a saint, though sadly not for his services to punctuation) described an updated version of Aristophanes’ system in which he rearranged the dots in order of height to indicate short (.), medium (·) and long (·) pauses respectively.

Books became an integral part of the Christian identity, acquiring decorative letters and paragraph marks (Credit: Alamy)

Moreover, Isidore explicitly connected punctuation with meaning for the first time: the re-christened subdistinctio, or low point (.), no longer marked a simple pause but was rather the signpost of a grammatical comma, while the high point, or distinctio finalis (·), stood for the end of a sentence. Spaces between words appeared soon after this, an invention of Irish and Scottish monks tired of prying apart unfamiliar Latin words. And towards the end of the 8th Century, in the nascent country of Germany, the famed king Charlemagne ordered a monk named Alcuin to devise a unified alphabet of letters that could be read by all his far-flung subjects, thus creating what we now know as lowercase letters. Writing had come of age, and punctuation was an indispensable part of it.

Cutting a dash

With Aristophanes’ little dots now commonplace, writers began to expand on them. Some borrowed from musical notation, inspired by Gregorian chants to create new marks like the punctus versus (a medieval ringer for the semicolon used to terminate a sentence) and the punctus elevatus (an upside-down ‘;’ that evolved into the modern colon) that suggested changes in tone as well as grammatical meaning. Another new mark, an ancestor of the question mark called the punctus interrogativus, was used to punctuate questions and to convey a rising inflection at the same time (The related exclamation mark came later, during the 15th Century.)

The three dots that had spawned punctuation in the first place inevitably suffered as a result. As other, more specific symbols were created, the distinction between low, medium and high points grew indistinct until all that was left was a simple point that could be placed anywhere on the line to indicate a pause of indeterminate length – a muddied mixture of the comma, colon and full stop. The humble dot was put under pressure on another front, too, when a 12th Century Italian writer named Boncompagno da Signa proposed an entirely new system of punctuation comprising only two marks: a slash (/) represented a pause while a dash (—) terminated sentences. The fate of da Signa’s dash is murky – it may or may not be the ancestor of the parenthetical dash, like those that surround these words – but the slash, or virgula suspensiva, was an unequivocal success. It was compact and visually distinctive, and it soon began to edge out the last holdouts of Aristophanes’s system as a general-purpose comma or pause.

enjoyed reading your post a lot.

Personally I find a Swiss Army knife to be a damned awkward tool to use for longer than enough to cut open a parcel or to open a bottle, or scrape out something stuck.

It blisters the hand, it's not a comfortable tool to use, it's a right royal pain in the situpon to keep clean and it most definitely does not like wet and muddy.

My tools get used. They get used in all weathers, they're quickly cleaned off, stropped and put by.

There's a great deal of satisfaction in knowing how. How to use a tool, how to get it to do what you want, without knackering either one's hands or patience.

A good plain knife, a decent axe, a reliable folding saw; there are many reasons why these have become the standard Bushcrafter's toolkit

I add a small pair of pruners to my pocket too.

.....and before you rail agin my axe comment @minamoto, my favourite and most used one is a joiner's Estwing roughing out axe. It rattled around the back of a joiner's van for a couple of years. He used it to take down gyproc and the like, until I spotted it and he said I could have it

Blessings on warthog1981, for he cleaned it and trued it up for me, and it's been a very good thing ever since

It's excellent for not only firewood, but rough carving, feathersticks and the like, and it's lightweight too, and never, ever given me a hotspot let alone a blister.

It blisters the hand, it's not a comfortable tool to use, it's a right royal pain in the situpon to keep clean and it most definitely does not like wet and muddy.

My tools get used. They get used in all weathers, they're quickly cleaned off, stropped and put by.

There's a great deal of satisfaction in knowing how. How to use a tool, how to get it to do what you want, without knackering either one's hands or patience.

A good plain knife, a decent axe, a reliable folding saw; there are many reasons why these have become the standard Bushcrafter's toolkit

I add a small pair of pruners to my pocket too.

.....and before you rail agin my axe comment @minamoto, my favourite and most used one is a joiner's Estwing roughing out axe. It rattled around the back of a joiner's van for a couple of years. He used it to take down gyproc and the like, until I spotted it and he said I could have it

Blessings on warthog1981, for he cleaned it and trued it up for me, and it's been a very good thing ever since

It's excellent for not only firewood, but rough carving, feathersticks and the like, and it's lightweight too, and never, ever given me a hotspot let alone a blister.

Interesting discussion.

Miracle and Decker in "The Complete Book of Camping" ( 1961) an American focussed book, discuss the ideal knife for the recreational camper on the fringes of the wilderness. I always remember their comments on the bowie knife: ideal for stabbing small bears or thick-chested men but if you carry it as an outdoors knife, you'll always be wishing you had an axe or a razor blade! Their recommended knife type resembled a Mora Companion.

Personally, the knife i use most is a SAK because that is what is always to hand. But I agree fully with what Toddy says about them. In my rucksack is a small puukko. I no longer routinely carry an axe or saw as most of my activities nowadays are in places where fires are inappropriate or illegal. The SAK opens tins, bottles and packaging, saws small branches, cuts cordage and bores holes. The puukko is shaving sharp and handles almost anything else.

ironically, axes and saws see most use at home, but I'm fortunate enough to live in a rural environment.

Miracle and Decker in "The Complete Book of Camping" ( 1961) an American focussed book, discuss the ideal knife for the recreational camper on the fringes of the wilderness. I always remember their comments on the bowie knife: ideal for stabbing small bears or thick-chested men but if you carry it as an outdoors knife, you'll always be wishing you had an axe or a razor blade! Their recommended knife type resembled a Mora Companion.

Personally, the knife i use most is a SAK because that is what is always to hand. But I agree fully with what Toddy says about them. In my rucksack is a small puukko. I no longer routinely carry an axe or saw as most of my activities nowadays are in places where fires are inappropriate or illegal. The SAK opens tins, bottles and packaging, saws small branches, cuts cordage and bores holes. The puukko is shaving sharp and handles almost anything else.

ironically, axes and saws see most use at home, but I'm fortunate enough to live in a rural environment.

Iknow?!?!??Imagineaworldwithoutspacesbetweenwords???orjoineduprepliesandresponses????????????????????????Itwouldbe???interestingtosaytheleast!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Butwedigress.....Itsreallyimportantograspabasicfundamentalconceptofthoughtandadheretoit!!!!Atleastthatswhatithink!?!??!Butwhataboutthehistoryofthe humblequestionmark????????????Makesthehashtag#################lookmundane!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!interesting read.....thanks.can you imagine trying to read these posts if they were written without spaces? it threw me slightly just reading your example

enjoyed reading your post a lot.

But the fact that you CAN read it is interesting. However, I've had a lot of experience in deciphering the scrawls of the barely literate. Someofitonthiswebsite!Iknow?!?!??Imagineaworldwithoutspacesbetweenwords???orjoineduprepliesandresponses????????????????????????Itwouldbe???interstingtosaytheleast!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!Butwedigress.....Itsreallyimportantograspabasicfundamentalconceptofthoughtandadheretoit!!!!Atleastthatswhatithink!?!??!Butwhataboutthehistoryofthe humblequestionmark????????????Makesthehashtag#################lookmundane!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Reading your posts you seem to have a rather narrow view of bushcraft. Now I would never describe myself as a bushcrafter but I do a lot of things that others would call bushcraft.mora knives are excellent and out perform many other so called super knives.buy 2 and look after them.a clipper and a heavy duty....axe though?.....not required anywhere in the uk....unless its just for fun purposes???

If I was to camp in my woodland for a few days I'd certainly take an axe. I'm more used to using one to split, shape and process wood to make things out of, not just for splitting wood for a fire.

One advantage of using an axe over a knife is several of my axes have only cost a few pounds each, even a mora costs more.

I tend to leave the small brash to rot down so I'd want to split some of the thicker, decent fire wood to start with.

Mind you, if it's just a small fire I'd just take a folding saw and cut half way through a log and split that way.

If it was a big fire or a large job then chainsaw and axe.

You can get by without an axe in the UK. You can get by without a knife too by using secateurs.mora knives are excellent and out perform many other so called super knives.buy 2 and look after them.a clipper and a heavy duty....axe though?.....not required anywhere in the uk....unless its just for fun purposes???

Or by just stopping at home and watching TV you don’t need any of those. Just an iPad to call Uber eats.You can get by without an axe in the UK. You can get by without a knife too by using secateurs.

You don’t really need a guitar to play cracking music either. But it’s far better than using a bottle half full with water or a triangle.

That is basically what I wrote first of all but thought I'd rein in my sarcasm!Or by just stopping at home and watching TV you don’t need any of those. Just an iPad to call Uber eats.

You don’t really need a guitar to play cracking music either. But it’s far better than using a bottle half full with water or a triangle.

I visited England only once in my life, many decades ago and didn't ignite a single fire there. That's why I am unsure if you have the same conditions like we find them in Germany. But I need one match to ignite a fire in a German forest. Not two of them, no knife, no axe, hatchet or saw.

And I taught that skill successfully to quite a few 10 to 12 years old boys.

The secret behind is that we usually start a fire with the dry twigs of the lower part of conifere trees, usually spruce or pine.

I simply choose the place for the camp not too far from a suitable tree of that kind.

I need robust hiking boots to section the needed sizes of firewood.

We usually carried a saw to make poles and tent stakes and a hatchet to hit them into the ground, but most of us just broke the firewood by hand or boot.

It's a bit dangerous though. If you step too strong onto a piece of wood the end can fly up and hit you at the head. But using tools is dangerous too if you don't know how to do it correctly.

If most wood is damp I dry it in a circle around the fire. I build some kind of fence around the fire.

We generally always tried to be as quiet as possible, and that's why we always tried to avoid the use of hatchet and saw.

I nowadays usually don't carry hatchet or saw unless I count with snow and ice, because that can make things pretty complicated. If everything is frozen to the ground and hidden by snow it isn't so easy to collect firewood and far better to use smaller dead standing trees, which usually burn better anyway.

I agree that in skillful hands all and everything can be done with a usual Swiss Army Knife. But although I usually count the weight of my equipment with letter scales or electronic kitchen scales I prefere to carry a pretty robust full tang knife with 11 cm blade length around because with that I am simply much much faster.

I think the Opinel No8 Carbone is more or less the minimum for a bushcraft all purpose knife. No7 may be OK for really advanced users but I usually recommend the No8.

The SAK can do the job as well. But in the evening I am usually not patient enough to gnaw with such a little tool around if I need to make tent stakes and especially poles. A Victorinox with saw might be an option though.

We usually don't talk in this forum about it, but yes, I admit to carry the Morakniv Garberg also as a potential weapon for self defence.

For many years I did carry just a Opinel No8 Carbone but had for the group a 600 g hatchet accessible, indeed mentally prepared to split someone who would try to attack my boys with the first strike the skull. For my own self defence the full tang knife seems to be dangerous enough if needed.

And I taught that skill successfully to quite a few 10 to 12 years old boys.

The secret behind is that we usually start a fire with the dry twigs of the lower part of conifere trees, usually spruce or pine.

I simply choose the place for the camp not too far from a suitable tree of that kind.

I need robust hiking boots to section the needed sizes of firewood.

We usually carried a saw to make poles and tent stakes and a hatchet to hit them into the ground, but most of us just broke the firewood by hand or boot.

It's a bit dangerous though. If you step too strong onto a piece of wood the end can fly up and hit you at the head. But using tools is dangerous too if you don't know how to do it correctly.

If most wood is damp I dry it in a circle around the fire. I build some kind of fence around the fire.

We generally always tried to be as quiet as possible, and that's why we always tried to avoid the use of hatchet and saw.

I nowadays usually don't carry hatchet or saw unless I count with snow and ice, because that can make things pretty complicated. If everything is frozen to the ground and hidden by snow it isn't so easy to collect firewood and far better to use smaller dead standing trees, which usually burn better anyway.

I agree that in skillful hands all and everything can be done with a usual Swiss Army Knife. But although I usually count the weight of my equipment with letter scales or electronic kitchen scales I prefere to carry a pretty robust full tang knife with 11 cm blade length around because with that I am simply much much faster.

I think the Opinel No8 Carbone is more or less the minimum for a bushcraft all purpose knife. No7 may be OK for really advanced users but I usually recommend the No8.

The SAK can do the job as well. But in the evening I am usually not patient enough to gnaw with such a little tool around if I need to make tent stakes and especially poles. A Victorinox with saw might be an option though.

We usually don't talk in this forum about it, but yes, I admit to carry the Morakniv Garberg also as a potential weapon for self defence.

For many years I did carry just a Opinel No8 Carbone but had for the group a 600 g hatchet accessible, indeed mentally prepared to split someone who would try to attack my boys with the first strike the skull. For my own self defence the full tang knife seems to be dangerous enough if needed.

Last edited:

As did I. I toned it down.That is basically what I wrote first of all but thought I'd rein in my sarcasm!

Last edited:

If it's sharp it doesn't matter what it is itl doHello everyone!

I'm newish to bushcraft and recently started spending all of my time in woods as I've got bored of the snobby atmosphere in wild camping and looking for a beginner knife and axe to experiment with before getting one of these beautiful handmade blades I keep seeing.

I've got experience in survival, foraging, 7 day + trips and fire making but the group's I've always been with have looked down heavily in carrying any form of blade so begrudgingly never spent much time learning about them and how to use the effectively.

I'm currently looking at an entry level £12 Mora and a £10 axe from Tool station (these are just for a weeks experimenting and learning remember)

I'm eager to hear from people if you have any recommendations for the type of knife and axe I use to start with.

Thanks

LPK!

moras though cheap are excellent knives.....the argument if not full tang is irrelevant.great steel...scandi grind.theyre made for use in harsh conditions.....conditions we will never..NEVER experience anywhere in the uk.use a knife what its DESIGNED for and a mora will hold its own with ANY knife.If it's sharp it doesn't matter what it is itl do

Similar threads

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 767

- Replies

- 25

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 42

- Views

- 5K