I thought it might be useful here to dwell a little on the nature of bees. Its very helpful to understand the types of bees and their lifecycle in order to manage them successfully.

There are basically three types of bees

Workers

Drones

Queens

Workers are infertile females and comprise most of the colony. They do all the food gathering, protection, hive maintenance and brood rearing. Most of the 70,000 bees in a colony are workers

Drones are males. They lack stings and also lack food gathering equipment. Their main role is to fertilise a new queen. A queen is only mated over a single period in her life over abut a week. She stores the sperm up and uses it thereafter and will not mate again.

The Queen is the only fertile female (once mated). There is only one queen per hive (with rare exceptions for a short period). Most queens only fly to mate - and again to swarm (split the colony) if a new queen is born. A queens role is to lay eggs. Lots of eggs - up to 1500 eggs per day.

This is what the eggs look like (little white threads).

Bee Eggs

Bee Eggs by

British Red, on Flickr

If the queen releases sperm and fertilises the egg, it will become a female worker egg. If an infertile egg is released, it becomes a drone. If the workers want a new queen, they will raise a special cell called a queen cup (although they also do this for "practice" and tear them down sometimes). When an egg is laid in such a cup, it is fed differently (with a substance known as Royal Jelly), this egg becomes a new queen.

This is a "queen cup"

Queen cup top of frame

Queen cup top of frame by

British Red, on Flickr

After an egg is three days old (for a worker egg) it hatches into a larvae - known as "unsealed brood". After six days the fed larva is sealed over. This is known as "sealed brood". 12 days later a young worker emerges.

You can see white, crescent shaped unsealed brood marked with a red arrow below. Sealed brood is marked with a blue arrow

Sealed and unsealed brood

Sealed and unsealed brood by

British Red, on Flickr

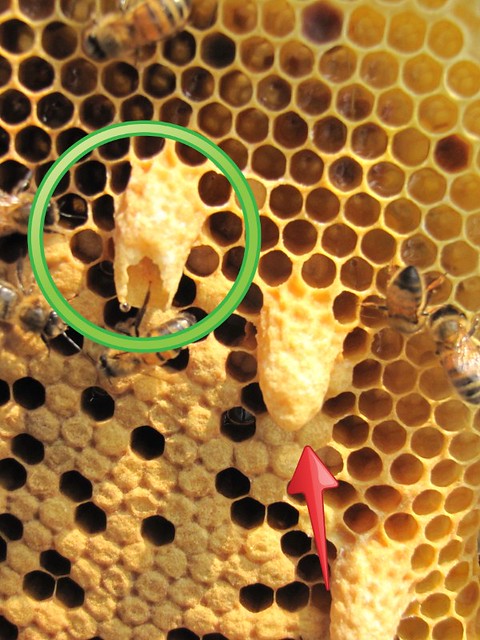

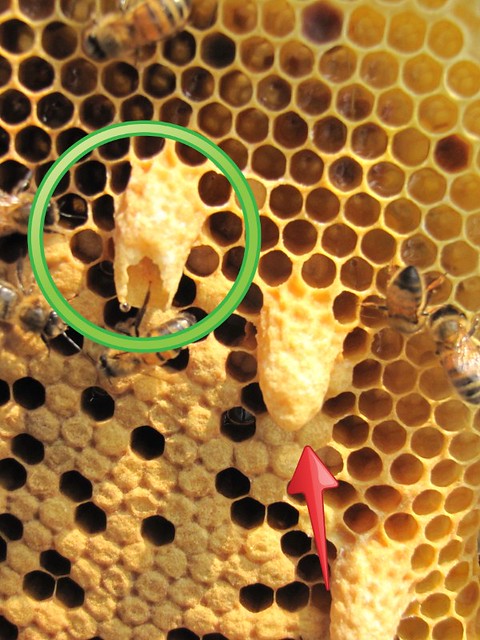

Drone timings are slightly different but similar. Drone brood has a very raised appearance - shown in the red circle below

Drone Cell

Drone Cell by

British Red, on Flickr

If your queen has not mated properly, she cannot fertilise eggs so all you will see is drone brood - no workers means no foraging so this is a real problem that needs to be addressed.

So, we have seen drones and workers. Periodically the workers will raise queen cups and the queen will lay in them. If the workers are happy with the queen and the hive, these cups will be torn down. If the bees feel crowded, or unhappy with the queen, they will raise the eggs in the queen cups into queen cells.

This is a queen cup

Incipient queen cup side of frame

Incipient queen cup side of frame by

British Red, on Flickr

In the green circle you can see this cup being "drawn out". The red arrow points to a queen cell that has been drawn out and sealed

Developing emergency queen cells

Developing emergency queen cells by

British Red, on Flickr

Over time the bottom of the queen cell becomes papery and brown and, after about 8 or 9 days a new queen will hatch

Queen cell near hatching

Queen cell near hatching by

British Red, on Flickr

If the old queen is present when a new queen is born, it is likely that the old queen will leave the hive with half or more of the old workers and find a new home - this is known as "swarming"

Swarm in air

Swarm in air by

British Red, on Flickr

Honey Bee Swarm

Honey Bee Swarm by

British Red, on Flickr

A beekeeper wants to avoid swarming - the loss of bees severely impacts honey production. The beekeeper will try to avoid this by artificially swarming (splitting) a hive where queen cells are found.

Sometimes an old queen will allow the new queen to take over - and even lay side by side with them - this is known as "supersedure".

Okay, so we understand a little about the bees lifecycle why does this matter?

Well, bees are going to want to swarm - it happens - as a beekeeper you cannot prevent it. It happens because your queen is getting old and not emitting enough "queen pheromone" to reassure her workers. It happens because the existing queen is poorly mated. It happens because the queen dies. If it happens that the works plan to create a new queen, queen cups will be created, laid in and turn to queen cells. If the queen dies, an existing worker egg will be fed differently and tuned into a queen cell (known as an "emergency" queen cell). If we just let that cell hatch, the emerging virgin queen will generally fight to the death with other virgin queens by stinging (queens generally only sting other queens). Unless supersedure is taking place, the old queen will generally swarm with up to 60% of the workers. The virgin queen will fly on a warm day and mate with up to 15 drones, repeating the process for several days. She will accumulate up to 6 million sperm and that is all she will use for the remainder of her life of up to 5 years If the weather is bad, the queen cannot fly and hence will become a sterile, drone laying queen. If the old queen has swarmed, and no eggs have been laid in the last 3 days to create an emergency queen, this can spell death for the colony. A clever beekeeper will introduce a frame of eggs from another colony in this circumstance - removing the drone laying queen. The workers will raise an emergency queen from the introduced eggs.

To prevent the loss of 60% of the bees, a beekeeper may well "artificially swarm" a colony raising queen cells. The old queen, some stores and workers are placed in a new hive. The old queen will lay eggs in the new hive and the workers lay in stores. In the old hive, the new queen will be born and mate. If eggs are found after a couple of weeks following the new queens birth, she is mated and fertile. The beekeeper now has a choice - keep two hives or re-unite the hives. To re-unite hives, the brood boxes are placed on top of one another separated by a sheet of newspaper. One queen is removed. The bees will chew their way through the paper and merge. If the bees were simply plonked together, they would fight treating it as an invasion. The paper allows their scents to mingle before they meet.

Normally in re-uniting, the older queen is removed (and destroyed), but this should not be done until it is certain that the new queen has successfully mated. If the new queen is a drone layer, the new queen can be removed and the old queen used, although it is probable that the hive will try to swarm again.

We used this procedure successfully this year to split our Buckfast colony. Unfortunately, the original queen is still not proving satisfactory to her workers and they have raised another queen cell, so rather than risk splitting the colony again, we are trying a different technique.

This technique involves using an "apidea" - a tiny beehive often used in mating queens.

Apidea

Apidea by

British Red, on Flickr

Once a queen cell had formed, we knew it had about 9 days to hatch. Approaching the hatching time, we captured the old queen, and gathered 2/3 of a cup full of workers and shut them up in the Apidea. The apidea contains some strips of foundation (wax) on three small frames and a lot of fondant (sugar based bee food). The apidea is kept in a cool shady building (a barn) and kept closed for three days. The bees have all the food they need - but no water, so a water mister is used twice a day to mist water through the grill. After three days, the apidea is placed outside and opened but with a queen excluder over the entrance. A queen excluder has precise slots that let a worker through but not a queen

Apidea

Apidea by

British Red, on Flickr

We took a look in the apidea today.

Open Apidea

Open Apidea by

British Red, on Flickr

You can seen the bees have begun creating comb on the miniature frames - and the queen is still there (circled)

Queen in Apidea

Queen in Apidea by

British Red, on Flickr

We can sustain the queen in this hive until we determine whether the new queen has hatched and mated. She should start laying eggs about 12 days after hatching. We need to let those eggs pupate and determine that we have worker brood, not just drone brood. If we have, then we have a vibrant new queen and the old queen can be disposed of.

If not, we can re-introduce the old queen having removed the drone layer.

If the new queen is laying well, one other thing we will do is mark her and clip the tip off one wing preventing her flying again. That way, if she attempts to swarm in the future, she will simply fall to the floor rather than fly off. The workers should then re-enter the hive rather than swarm.

Hopefully this (brief) introduction shows that beekeeping can be quite scientific, and the tendencies of the bees can be manipulated and used to replace queens carefully and even create new colonies. We are still very much novices, but discovering how to monitor and understand the lifecycle of bees is a fascinating journey.

Red