DIY Moth Trap Results :)

- Thread starter Broch

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To be honest RV it's as much as I can do to identify them so that we are getting a species count. We're trying to do a fairly comprehensive bio-diversity survey of the place so we can't afford to get too deep into any one area (there's only two of us covering 20 acres). The problem really is that every time we start into an new area we discover how vast it is (900 species of macro moth for example!). I know less now than when I started because I've learnt there's far more to know

All we can really do is take samples - birds, flowers, butterflies, moths .... so in five, ten, fifteen years time we can compare and see change.

All we can really do is take samples - birds, flowers, butterflies, moths .... so in five, ten, fifteen years time we can compare and see change.

This is good to read. You really are learning about your local environment.

I hope that you keep the very best of written records.

Earning a PhD in Biology has much the same effect. I know one hell of a lot about very, very little.

I hope that you keep the very best of written records.

Earning a PhD in Biology has much the same effect. I know one hell of a lot about very, very little.

Yes, I've constructed a database of what we find, when and where. It records when we first identify anything and when we last saw it, so, for example, it shows we haven't had any Greenfinches here for the last four years  . We also have field-books we take copious notes in.

. We also have field-books we take copious notes in.

Interesting stuff.

Late last year I bought a 5 acre meadow and since then I have been taking (mental) notes of what is there - flora and fauna - and thinking what I can do to enhance the environment. Since I have had it less than a year I am already finding it astonishing and surprising what the different seasons are bringing. And this piece of land was hardly unknown to me before I purchased it - I'd walked across it many times when out for a ramble in previous years. But now it's mine I have a keener interest and I am very surprised and pleased by exactly what I'm noticing.

I haven't gone so far as making actual physical notes or a database to track changes.

I think I probably should.

Broch - I'd be grateful for any advice on how you went about doing yours. Where you decided to start, how you record findings, what you do track and trace changes, etc.

Late last year I bought a 5 acre meadow and since then I have been taking (mental) notes of what is there - flora and fauna - and thinking what I can do to enhance the environment. Since I have had it less than a year I am already finding it astonishing and surprising what the different seasons are bringing. And this piece of land was hardly unknown to me before I purchased it - I'd walked across it many times when out for a ramble in previous years. But now it's mine I have a keener interest and I am very surprised and pleased by exactly what I'm noticing.

I haven't gone so far as making actual physical notes or a database to track changes.

I think I probably should.

Broch - I'd be grateful for any advice on how you went about doing yours. Where you decided to start, how you record findings, what you do track and trace changes, etc.

How did you make the moth trap? I'd be interested in making one myself and seeing what I get.

I've just bought a book on butterflies and moths that was a lockdown project, but I've not got round to much study yet.

I've just bought a book on butterflies and moths that was a lockdown project, but I've not got round to much study yet.

I have the greatest respect for people who take careful inventory of the flora and fauna on the land.

We may or may not see much change in our lifetimes but such is inventory. The journey is the reward.

We may or may not see much change in our lifetimes but such is inventory. The journey is the reward.

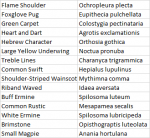

Last night's catch:

Favourite this time is a toss between the Light Emerald, The Brussels Lace and the Peppered Moth; I'll go for the Brussels Lace

| White Plume | Pterophorus pentadactyla |

| Brussels Lace | Cleorodes lichenaria |

| Peppered Moth | Biston betularia |

| Flame | Axylia putris |

| Light Emerald | Campaea margaritata |

Favourite this time is a toss between the Light Emerald, The Brussels Lace and the Peppered Moth; I'll go for the Brussels Lace

Attachments

How did you make the moth trap? I'd be interested in making one myself and seeing what I get.

I've just bought a book on butterflies and moths that was a lockdown project, but I've not got round to much study yet.

I've used three 3W LEDs covering the main light spectrum that moths are attracted to - so UV to a blue/green. They're mounted on an aluminium box that contains a lithium battery from an old strimmer and current controlling electronics. That's all mounted on a plastic storage box with acrylic flaps angled down - I'll take some photos tomorrow; it will be far more clear

Though, to be honest, you can get good results by shining a 'white' light onto a white sheet. Bright LED torches are quite good.

Interesting stuff.

Late last year I bought a 5 acre meadow and since then I have been taking (mental) notes of what is there - flora and fauna - and thinking what I can do to enhance the environment. Since I have had it less than a year I am already finding it astonishing and surprising what the different seasons are bringing. And this piece of land was hardly unknown to me before I purchased it - I'd walked across it many times when out for a ramble in previous years. But now it's mine I have a keener interest and I am very surprised and pleased by exactly what I'm noticing.

I haven't gone so far as making actual physical notes or a database to track changes.

I think I probably should.

Broch - I'd be grateful for any advice on how you went about doing yours. Where you decided to start, how you record findings, what you do track and trace changes, etc.

Please excuse this rather long and meandering answer; it has become something of a passion

I decided that it was fundamental, before making any changes to a piece of land, to understand what is there and form my management plan around that. So, in my case, whereas I want the best bio-diversity the land can support that must not be at the expense of what is already there. For me, that means preserving some of the darker, more enclosed, damp areas that have mosses, lichens, liverworts, and fungi whilst opening up some areas on the edge to create a transition. I also have a no-introductions policy – so anything that develops is because it was there, supressed or dormant, or arrives naturally.

I learnt a lesson some 26 years ago when I excluded all grazing from a small woodland to encourage an understory – we lost all the primroses! However, in balance, we now have some dense understory for a wide range of wildlife and bluebells are back.

I divided my land (not physically but on a plan) into areas that I felt may have differing species – I’ve probably gone too far but it allows me to record differences between areas on the edge of the wood and in the centre, or along the tracks, for example.

I’ve also learnt, very quickly, that even in a relatively small area there are too many species to identify and record. So, we stick to learning a few at a time and keep going over the same material again and again – double checking our ID and knowledge. We have started with relatively easy ones – we’re quite competent with the birds and mammals, a few reptiles and lizards; there aren’t many species so they’re easy. I haven’t started with bats and will get a bat detector for that.

I’ve always thought I knew a fair bit about plants, but you’ll soon discover there are variations and hybrids as well as orders of magnitude more species than you first thought. But, don’t let that put you off or dissuade you – stick to the more obvious ones first and before you know it you’ll be down on your knees looking at the beautiful forms of some flowers too small to appreciate without a magnifying glass.

If you can handle Excel it makes a good platform for recording your data – you can search and sort it quite easily; although you could do that with Word as well. If you were inclined, you could change the Excel sheets into an Access database at a later stage but it’s not necessary.

I have created a sheet per topic – I’ve chosen:

- Trees

- Plants, shrubs and vines

- Lichens

- Fungi

- Birds

- Mammals

- Reptiles and amphibians

- Insects and spiders

- Moluscs and worms

For each I record the common name, the scientific name, where it was seen, when it was first seen and when it was last seen. I have a final field for general notes where I might record a specific diagnostic feature that helps me remember a species – or other information of interest.

We’ve been on a few Field Studies Council courses – me on Fungi and my wife on woodland plants and ferns; they really do get you into the topic and are good value for money. We’re also members of our local Field Studies Group that arrange workshops each year – we’ve done meadow bugs, and dragon flies and damsel flies, as well as days out doing surveys with people with a lot more knowledge than us.

I got a bit frustrated by it all when I realised the topic was far bigger than I expected (there are 300 species of hover fly, 900 species of macro moths, in the order of 27,000 species of insects in the UK) but, now, I’ve accepted I can only identify some main ones – indicators if you like – and will learn others as opportunity arises.

So, I think, my main advice is: relax, enjoy it, and accept the subject matter is too huge for one lifetime, and learn something new each time you go out

Again, apologies for the length of the post, but, if you're ever in the area, get in touch and I'll gladly show you what we've done.

Not all living things live in all places, that should be clear.

What you likely see are many "indicator species" which have specific ecological niche requirements

which are satisfied in the land that you are on. In short, they can't live anywhere else.

Deal is, you needn't learn them all. Learn the expected. Research the unexpected.

Your Peppered Moth, Biston betularia, is the globally famous example of population gene frequencies.

We had lab exercises built upon models of that lovely beast.

British Columbia has more biodiversity than all of the rest of Canada.

As indicators, I taught about 80 species of plants. Their very existence

was tied to water, soil composition, nutrients and seasonal climate changes.

Think "cactus." Without seeing, what can you say about the ecology of cacti?

The same sense applies to your moths.

What you likely see are many "indicator species" which have specific ecological niche requirements

which are satisfied in the land that you are on. In short, they can't live anywhere else.

Deal is, you needn't learn them all. Learn the expected. Research the unexpected.

Your Peppered Moth, Biston betularia, is the globally famous example of population gene frequencies.

We had lab exercises built upon models of that lovely beast.

British Columbia has more biodiversity than all of the rest of Canada.

As indicators, I taught about 80 species of plants. Their very existence

was tied to water, soil composition, nutrients and seasonal climate changes.

Think "cactus." Without seeing, what can you say about the ecology of cacti?

The same sense applies to your moths.

Lots of stuff

Lovely. Thanks very much for that.

There were lots of thoughts and ideas in that which hadn't occurred to me.

Very much appreciated.

How did you make the moth trap? I'd be interested in making one myself and seeing what I get.

I've just bought a book on butterflies and moths that was a lockdown project, but I've not got round to much study yet.

Photos, as promised:

Version 1 has an internally mounted Lithium battery from an old strimmer. Version 2 I made for my son today with a home-made plug so he can connect his Makita batteries to it. And the final photo, version 1 mounted on the collection box. The paler LED is the UV one - it's just as bright but not within the camera or our vision spectrum.

Version 1:

Version 2:

And Version 1 mounted on the box:

That's a lot of space for 2 (lucky) peopleTo be honest RV it's as much as I can do to identify them so that we are getting a species count. We're trying to do a fairly comprehensive bio-diversity survey of the place so we can't afford to get too deep into any one area (there's only two of us covering 20 acres). The problem really is that every time we start into an new area we discover how vast it is (900 species of macro moth for example!). I know less now than when I started because I've learnt there's far more to know

All we can really do is take samples - birds, flowers, butterflies, moths .... so in five, ten, fifteen years time we can compare and see change.

OLO

www.onelifeoverland.com

Just a quick update if people are interested; we have now identified 57 species of macro moth

I've made contact with the county recorder who has been very helpful with a few difficult identifications.

I remain in awe with the endless variety of pattern and colour when studied closely!

One of my favourites, a Black Arches (Lymantria monacha):

I've made contact with the county recorder who has been very helpful with a few difficult identifications.

I remain in awe with the endless variety of pattern and colour when studied closely!

One of my favourites, a Black Arches (Lymantria monacha):

Hello everyone, when i was a young lad my granddad new a chap that collected moths and butterflies. He had an astounding collection, all mounted ,(set). He had a huge cabinet full of British butterflies. All recorded with dates, place ,common name, and scientific name etc. I used to love going to his home, when he would show me how to mount them and display them. His father had a collection of stuffed birds. That he collected from around the world. My granddads friend had also collected moths and butterflies from India and the north of Africa when he was in the army. I think this must have been WW1 era because Tom was 93 years old when he passed away. He was still out collecting butterflies and moths when he was 92 years old. It was meeting Tom that started my interest in the countryside and nature. I know that this is not very pc and is frowned upon these days, but this was a different era and is how things were done in those times. My late wife's uncle who at one time had been a game keeper, had a huge collection of birds eggs. The late great Peter Scott had visited his home to view his collection. I think that after he died his egg collection was donated to a museum. But i don't know which one. Anyway i digress, what i wanted to say is you can attract moths to your garden or when out camping etc by getting them drunk. Ok what you do is in an old pan heat up a tin of black treacle add a few spoon full's of sugar tbl spoons. Now comes the hard part you need amyl acetate known as pear drops. You used to be able to buy small amounts from the chemist. This makes it smell like the pear drop sweets. keep stirring until the sugar i dissolved. Then add some beer. let it cool down. You can then take it to your desired place, paint a small strip onto tree trunks, fence posts etc. Check every hour or so with a torch. The pear drop smell attracts them and the beer gets them drunk so they don,t fly away.

I have just completed my 2021 records for the county recorder - I have now identified 116 species just in the area around the house.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 221

- Views

- 13K

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 37

- Views

- 5K