N

Nomad

Guest

A chat elsewhere about finding north using a wristwatch and the sun led to the Viking sunstone thing, which can purportedly be used to find the direction of the sun in overcast conditions. My interest was piqued, so I did a bit of research and bought one. In this thread, I'll document what I learn about it, and hopefully find a way to make use of it.

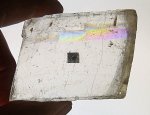

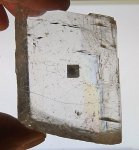

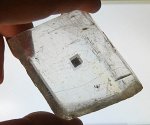

Here it is...

I'm not one for anthropomorphising things, but I decided that it's my pet rock, and a good Norse name was appropriate, so I've called it Baldur, Giver Of Light.

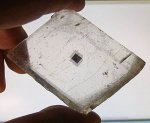

It's about 17mm thick, 41mm wide and 53mm long. It's rhomboidal in all three axes and the measurements are perpendicular to the surfaces. The little squares in the middle of three sides are bits of self-adhesive copper tape. I added these after seeing a couple of videos on YouTube where the stone had been marked with a marker pen. (Copper is opaque, doesn't rub off, and I happened to have the tape handy.)

The actual material is crystallised Calcium Carbonate, and this particular variety is also known as Iceland Spar and "optical Calcite". It differs from other varieties in that it's more or less optically clear - it's like a lump of plate glass that's been knocked about a bit. In the photo above it looks more cloudy than it really is - it's actually quite glassy and clear.

Iceland Spar has has some properties that are worthy of note. One is that it's brirefringent, which means it refracts light at two angles simultaneously (unlike glass, water, etc, which refract at one angle). It also transmits or blocks polarised light depending on its orientation, and it does this in a particular way - as the orientation changes, one or the other of the refracted rays becomes suppressed. Moreover, there is a null point where both rays are partially suppressed, and thus both still visible.

While experimenting with the stone, the following were also observed...

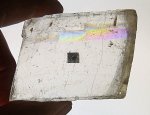

The following series of photos show what happens when the orientation of the stone is varied when it's in the presence of polarised light. The light source is an LCD computer monitor showing a field of white. The change in orientation is rotation of the stone while keeping the viewing surfaces parallel to the screen (ie, rotated like the hands on a clock). The copper square is on the far side of the stone from the viewer.

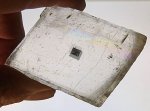

Here, we can see only one image of the copper square - the other has been suppressed due to the polarisation effect of the stone...

The stone is rotated about 20-25°, and the other image starts to appear above the first one...

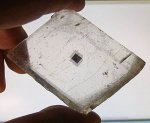

At about 45° rotation, both images have similar density - the null point mentioned earlier...

Continuing with the rotation to about 65-70°, the first image (the lower one) starts to fade...

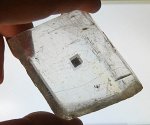

And at 90°, the second image is all we can see...

The effect repeats for each 90° rotation, meaning there are four orientations that give the balanced double image in the third photo.

I also did an experiment with non-polarised light and a polarisng filter as used in photography. Holding the filter on the side of the stone receiving the light, and rotating either the stone or the filter, resulted in the same effect as shown above. When looking through the stone without the filter, at non-polarised light, the dual image does not change when the stone is rotated - you always see the null point.

It is clear that, if the stone is rotated relative to the orientation of polarised light, the dual image transmission / suppression effect works. The next step is to try and work out how this can be applied in the field.

Without going into too much detail (lest I trip over inaccuracies), polarisation with sunlight is like this...

One conclusion can be drawn right away. It is not used to scan the sky in a random manner and, all of a sudden, something happens and you're looking towards the sun. This is because the dual image (photo 3 in the sequence above) is apparent when looking at the sun with stone at any orientation, and when looking at 90° to the sun when the stone is rotated a particular way (in any of four orientations).

In other words, the stone tells you something when you rotate it, and the only thing it tells you is whether or not it's pointed at polarised light.

It then becomes a question of how you interpret what you see. Basically, you have to 'read' the transmission / suppression effect. From my limited field testing so far, it is difficult to rotate the stone and see small changes in the dual image - this is what you would see if you were fairly close to the azumith of the sun, such that the light was only slightly polarised. On the other hand, when looking directly at the polarised band, the change in the dual image is striking.

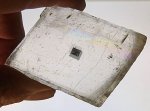

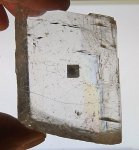

Have a look at these three photos...

Image nearest thumb is stronger.

Images balanced - null point.

Image nearest thumb is weaker.

These were taken in sunny conditions, late afternoon, with the sun roughly 90° to the direction of view (I didn't check and wasn't sure of what I was doing - this was my first play with it to see what happened). In this case, I'm looking through the 41mm thickness of the stone, which is why there is greater separation of the images. When I rotated around towards the sun, the disparity in image density in the third photo reduced.

I did another experiment earlier this evening, a little after sunset. In this case, I held the stone above my head, looked through it towards the zenith, and rotated it. The image transmission / suppression effect, even in poor light, was obvious - the words in my head at the time were 'clear as day'.

It could be argued that the stone can be used to find the direction of the sun (rather, the vector that passes through the sun and the observer) by looking for the direction where the dual image shows no change when the stone is rotated. However, so far, my feeling is that this is quite difficult to detect as you get close to the direction of the sun - you could be 20° off and barely see anything. By contrast, pointing the stone at polarised light and rotating it results in an obvious change, such that it's easier to be sure that you're on the band of polarised light. It seems that, when you're pointing it in the right direction, you get the full loss of one image and full density of the other. As I mention, I don't how accurate my daytime test was in terms of azimuth - the LCD monitor test was later. The twilight test was after the LCD test, and I had the same complete switch from one image to the other.

So, for now, I'm going to continue looking for the polarised light, knowing that the sun is not in that direction. If that can be reliably detected, it's then a case of finding the line that intersects the two azimuths to polarised light on the horizon, and that line will be the vector between the sun and the observer. I've still to try and work out how to find the direction to the sun from the vector.

Here it is...

I'm not one for anthropomorphising things, but I decided that it's my pet rock, and a good Norse name was appropriate, so I've called it Baldur, Giver Of Light.

It's about 17mm thick, 41mm wide and 53mm long. It's rhomboidal in all three axes and the measurements are perpendicular to the surfaces. The little squares in the middle of three sides are bits of self-adhesive copper tape. I added these after seeing a couple of videos on YouTube where the stone had been marked with a marker pen. (Copper is opaque, doesn't rub off, and I happened to have the tape handy.)

The actual material is crystallised Calcium Carbonate, and this particular variety is also known as Iceland Spar and "optical Calcite". It differs from other varieties in that it's more or less optically clear - it's like a lump of plate glass that's been knocked about a bit. In the photo above it looks more cloudy than it really is - it's actually quite glassy and clear.

Iceland Spar has has some properties that are worthy of note. One is that it's brirefringent, which means it refracts light at two angles simultaneously (unlike glass, water, etc, which refract at one angle). It also transmits or blocks polarised light depending on its orientation, and it does this in a particular way - as the orientation changes, one or the other of the refracted rays becomes suppressed. Moreover, there is a null point where both rays are partially suppressed, and thus both still visible.

While experimenting with the stone, the following were also observed...

- The direction between the two refracted rays is constant - the direction of the divergence rotates if you rotate the stone.

- When placed on a line drawn on some paper, such that the line extends beyond the stone, and then viewed perpendicular to the surface of the stone, it appears that one refracted ray is near to perpendicular through the stone, while the other is noticeably displaced.

- Based on measurements of my stone, the size of the copper squares, and observation of how much the images displace, the separation of the images is about 1.3mm per 10mm of thickness of the stone. This is useful to know when deciding what sort of size of mark to apply to a given stone. Since I arbitrarily cut the copper tape to around 6mm squares, when viewed through the 17mm thickness with both images visible, I get a noticeable overlap which appears as a smaller dark square in the middle.

The following series of photos show what happens when the orientation of the stone is varied when it's in the presence of polarised light. The light source is an LCD computer monitor showing a field of white. The change in orientation is rotation of the stone while keeping the viewing surfaces parallel to the screen (ie, rotated like the hands on a clock). The copper square is on the far side of the stone from the viewer.

Here, we can see only one image of the copper square - the other has been suppressed due to the polarisation effect of the stone...

The stone is rotated about 20-25°, and the other image starts to appear above the first one...

At about 45° rotation, both images have similar density - the null point mentioned earlier...

Continuing with the rotation to about 65-70°, the first image (the lower one) starts to fade...

And at 90°, the second image is all we can see...

The effect repeats for each 90° rotation, meaning there are four orientations that give the balanced double image in the third photo.

I also did an experiment with non-polarised light and a polarisng filter as used in photography. Holding the filter on the side of the stone receiving the light, and rotating either the stone or the filter, resulted in the same effect as shown above. When looking through the stone without the filter, at non-polarised light, the dual image does not change when the stone is rotated - you always see the null point.

It is clear that, if the stone is rotated relative to the orientation of polarised light, the dual image transmission / suppression effect works. The next step is to try and work out how this can be applied in the field.

Without going into too much detail (lest I trip over inaccuracies), polarisation with sunlight is like this...

- If you look straight at the sun, or directly away from the sun, there is no polarisation.

- If you look in a direction that's at 90° to the direction of the sun, there is lots of polarisation.

- If the sun is directly overhead (we're near the equator), the polarised light is spread out all around on the horizon.

- If the sun is on the horizon, the polarised light is at two points on the horizon that are +/-90° away from the sun's azimuth, and spreads out in a band across the sky between these two points, passing through the zenith as it goes.

- If the sun is at an intermediate position (including due south or north if we aren't near the equator), then the polarised band takes a relatively abstract path across the sky, not unlike a curved arch that has been tilted at an angle, such that the arch is facing the sun. Note that the arch still intersects the horizon at two points.

One conclusion can be drawn right away. It is not used to scan the sky in a random manner and, all of a sudden, something happens and you're looking towards the sun. This is because the dual image (photo 3 in the sequence above) is apparent when looking at the sun with stone at any orientation, and when looking at 90° to the sun when the stone is rotated a particular way (in any of four orientations).

In other words, the stone tells you something when you rotate it, and the only thing it tells you is whether or not it's pointed at polarised light.

It then becomes a question of how you interpret what you see. Basically, you have to 'read' the transmission / suppression effect. From my limited field testing so far, it is difficult to rotate the stone and see small changes in the dual image - this is what you would see if you were fairly close to the azumith of the sun, such that the light was only slightly polarised. On the other hand, when looking directly at the polarised band, the change in the dual image is striking.

Have a look at these three photos...

Image nearest thumb is stronger.

Images balanced - null point.

Image nearest thumb is weaker.

These were taken in sunny conditions, late afternoon, with the sun roughly 90° to the direction of view (I didn't check and wasn't sure of what I was doing - this was my first play with it to see what happened). In this case, I'm looking through the 41mm thickness of the stone, which is why there is greater separation of the images. When I rotated around towards the sun, the disparity in image density in the third photo reduced.

I did another experiment earlier this evening, a little after sunset. In this case, I held the stone above my head, looked through it towards the zenith, and rotated it. The image transmission / suppression effect, even in poor light, was obvious - the words in my head at the time were 'clear as day'.

It could be argued that the stone can be used to find the direction of the sun (rather, the vector that passes through the sun and the observer) by looking for the direction where the dual image shows no change when the stone is rotated. However, so far, my feeling is that this is quite difficult to detect as you get close to the direction of the sun - you could be 20° off and barely see anything. By contrast, pointing the stone at polarised light and rotating it results in an obvious change, such that it's easier to be sure that you're on the band of polarised light. It seems that, when you're pointing it in the right direction, you get the full loss of one image and full density of the other. As I mention, I don't how accurate my daytime test was in terms of azimuth - the LCD monitor test was later. The twilight test was after the LCD test, and I had the same complete switch from one image to the other.

So, for now, I'm going to continue looking for the polarised light, knowing that the sun is not in that direction. If that can be reliably detected, it's then a case of finding the line that intersects the two azimuths to polarised light on the horizon, and that line will be the vector between the sun and the observer. I've still to try and work out how to find the direction to the sun from the vector.

Last edited by a moderator: