Bushcraft Basics Series

So, I’ve just come back from another amazing WinterMoot, and as ever, it was great fun, full of learning and laughs. The thing I love about the Moots is that there is such a diversity of knowledge and experience. Some people are lifelong outdoorsmen & women, and others are just starting their journey into this incredible hobby.

As it often does at these kinds of gatherings, the conversation turns to the kit as people proudly show off their new knives, bags, axes and fire kits. All of us talking about the reasons why we preferred one over the other.

If you have been into this hobby for a while, I’m sure you can all point to the stalwart model of the Morakniv Companion or one of Hultafor’s knives. But this got me thinking about the features we should look for and what makes a good beginner’s knife for bushcraft. Have we picked the right one?

At its very essence, a knife is a sharp piece of metal with a handle attached so we don’t cut ourselves when using it. But from there on out, there are many questions to ask. Just asking a few questions will make the difference between getting the knife we need or ending up with something unfit for purpose.

Unfortunately, there is no one knife to rule them all; that’s why there are so many on the market and so many shops and online stores that make a living from selling them.

There will always be some compromise with a single knife. Don’t worry, though. This will enable you to grow a collection over time; Ha Ha.

As this is a beginner’s knife article, I want to pitch this to the more affordable end of the spectrum. A knife that you can use, and dare I say, abuse a little as you learn the techniques, for, sharpening, using, and storing.

So here we go, a few things to consider when buying your first bushcraft knife.

What will its main job be

What will your knife mostly be used for?

Will it be for carving, food preparation, skinning game or camp chores?

Once you know this, you can start making choices about which knife to pick.

Most knives used for carving will have a shorter blade and are slimmer in width. This gives you more control and enables you to make more detailed cuts and tighter turns, which is very useful when carving a spoon, notch or boring a hole into something.

Food preparation requires a thinner blade to allow ease of cutting through root vegetables and the like. Having flexibility in the blade is useful when gutting, cleaning and filleting fish. Skinning game can be easier with a smaller blade which helps with the dexterity needed for those finer cuts, avoiding damage to the hide or piercing organs.

For camp chores, a thicker, sturdier blade will be favoured for its resilience. This knife can be used to split larger sticks down for kindling, hack out notches, or quickly remove material from sticks for tent pegs or pot stands.

Handle and blade dimensions.

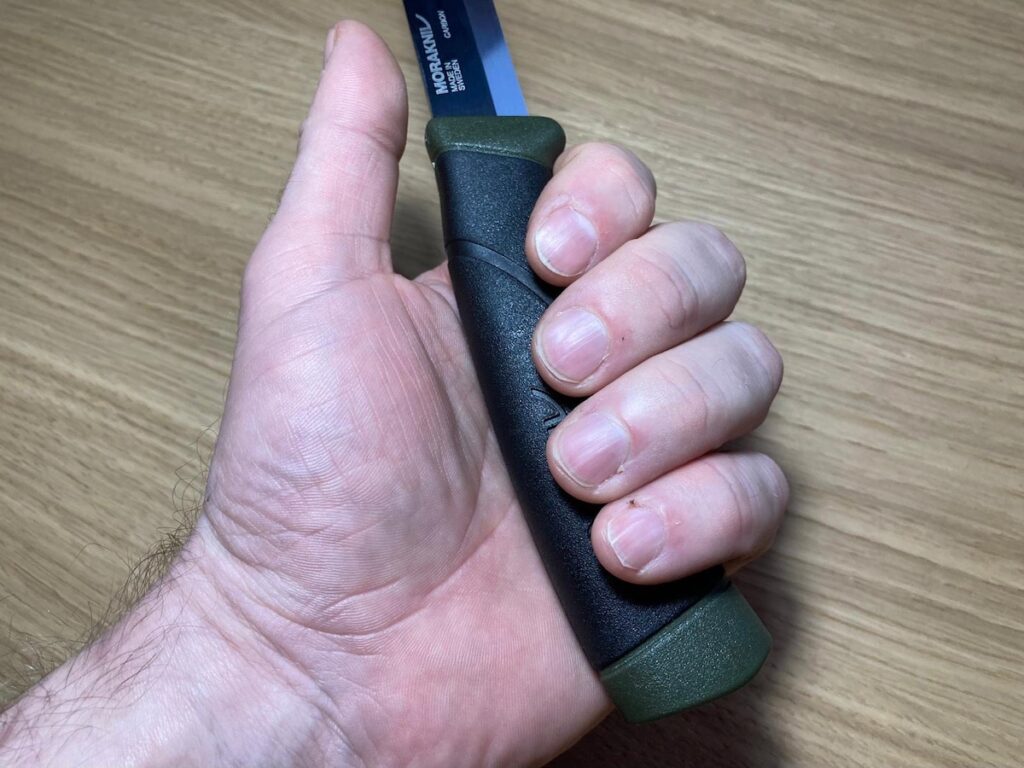

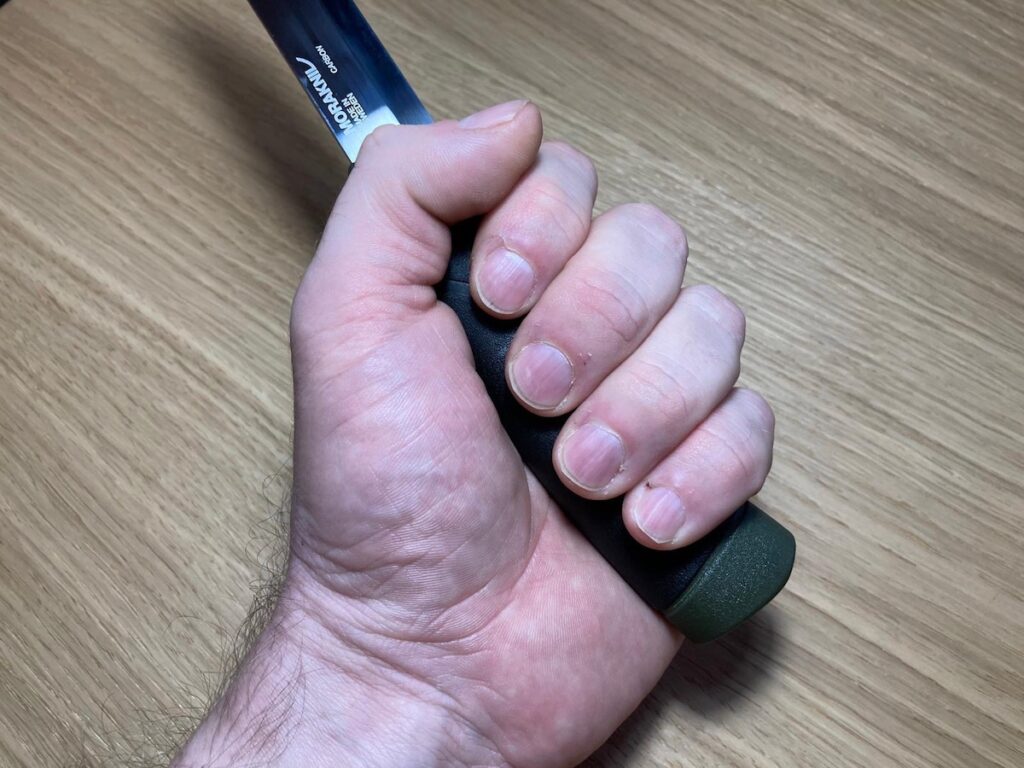

Good proportions are important with knife handles. Having a handle that is too big or small for your hand can cause fatigue, aches and hot spots. You should be able to grip the handle completely with no overhang of your fingers, and the knife should feel full in your hand. A good knife should almost feel like part of you. There shouldn’t be any tight angles or flat areas as this, too, can lead to discomfort. Try holding the handle in several orientations to check if it’s comfy enough to make different cuts.

The accepted rule of thumb for a bushcraft sheath knife blade length is roughly the width of your hand, give or take a bit.

Blade steel.

The steel your blade is made from can affect the way it sharpens and the way it reacts in different environments.

Carbon blades are easier to sharpen in the field and can be made very sharp. They will, however, need to be sharpened more frequently. Using a strop little and often can help to maintain the edge between sharpening sessions. In damp conditions, carbon blades will also rust quickly if they are not looked after. Making sure you wipe your blade dry and apply an oil or grease in a thin protective layer will keep corrosion at bay.

Stainless blades are better for wet conditions. It is a great steel to take with you when canoeing or doing bushcraft by the coast. Remember, though, that it’s called Stain-Less and not Stain-Not. If you are near salt water in particular, after a while, you may notice some corrosion. Due to stainless steel having added metals such as Chromium, the steel is often harder and, as a result, may be trickier to sharpen when out and about.

Sharp or rounded spine.

The back of your knife (spine) can sometimes be sharp at 90 degrees. This can be very useful if you want to strip bark while keeping your blade edge in good order. It can also be used to strike your ferrocerium rod (modern flint & steel), and thus, there is no need for a separate striker. On the flip side, if you are carving and putting pressure on the spine of your knife for extended periods of time, this can lead to cuts and abrasions. Some people use a file to grind the spine flat in one area to allow for both uses.

Sheath

Most bushcraft knives come with either a leather or some kind of plastic sheath. Leather is good-looking, malleable and traditional. Plastic or Kydex (a type of thermos plastic favoured by custom makers) sheaths are hard-wearing and waterproof. Plastic sheaths come in a variety of colours; this can be useful when wanting to quickly distinguish your knife from others; it’s also easier to locate in leaf litter or just as a personal expression.

Some sheaths attach to the belt with a loop keeping it close to the body; others have a dangler, which allows the sheath and knife to swing around slightly. This can be great if you are sitting in a chair or canoe, although sometimes it can become annoying when walking for any distance.

The last way I’ve seen knives being carried in the sheath is on a lanyard around the neck or across the body. This really comes into its own when wearing bulky clothing in colder months and means you don’t have to lift your jacket to gain access to your knife. You can achieve this by simply threading a cord through the belt loop or some sheaths will have a D ring on that loop to make this modification easier.

Many of the Nordic mass-produced models have a way of attaching the sheath to a button. Mostly carried on the chest on the button of your breast pocket, this is favoured by the military.

You could, however, fashion your own belt loop, which has a button on it, which is great for easy removal of your knife when you wish to pack it away, give it to someone else or so that it doesn’t dig into you while having that well-earned afternoon nap. I think Morakniv make one now, but they are tricky to find and sometimes a bit expensive for what they are.

My recommendations

In my opinion, Morakniv has hit the nail on the head with their Companion series knives. They offer nearly all the things we are looking out for. They also have many great alternatives available.

If you have larger hands and want something with a little more heft, then the Companion Heavy Duty is for you. With its slightly bigger handle and thicker blade, this is a great choice for around £16.

For use around salt water the Stainless-steel version of the Companion over the carbon steel is your go to for around £10

For carving and lighter camp tasks, the Morakniv 510 model is amazing and around £11

If you wanted something smaller and lighter with added grip safety in the handle, then I recommend the Hultafors Craftsman’s knife. This is a great knife for younger bushcrafters, with proper guidance and supervision. These can be found for as little as £8 online.

Last thoughts

Choosing your first bushcraft knife comes down to understanding its primary use, selecting the right blade material, and ensuring a comfortable handle. While there’s no perfect knife for all tasks, affordable options like the Morakniv Companion and Hultafors Craftsman’s Knife provide excellent starting points. Pick wisely, and happy bushcrafting!

BEN CLARKE

My formative years were spent reading the SAS survival handbook and watching Ray Mears on tracks on the telly. Learning a lot about the outdoors from my grandad who was a park ranger.

My first love of bushcraft will always be lighting fires, learning the techniques and history. When I was eight, I nearly burned the house down after hiding a lit candle from my parents under the bed. My sister luckily told on me. I can say that I’m a little safer with my pyromaniac tendencies now.

After being a scout and doing the duke of Edinburgh awards, I now practice my bushcraft skills with a great group of friends from all over the country.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.